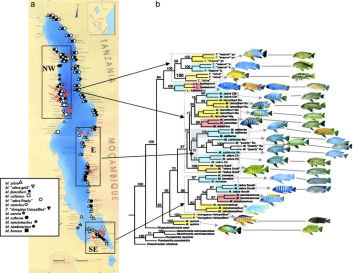

This is a map of where to find fish in Lake Malawi. The 3 million year old basin lapping against the ‘The Warm Heart of Africa”s eastern border has a unique biodiversity of cold-blooded residents.

This is a map of the voter breakdown during Malawi’s fourth multi-party election, in 1993.

And this is a map showing the start point of every patient arriving for surgery at the Fistula Care Centre in the capital city, Lilongwe: hundreds of women from dark corners of small rooms in rural villages across the country, living with the permanent incontinence of obstetric fistula. Usually in isolation, locked out of society mourning their baby, their dignity, their place in society.

Maps can teach you a lot of different things, but of course it depends what you’re looking for.

In the last month Lifebox has joined two trips to Malawi, plotting a route directly towards the country’s anaesthesia providers. Without them the fish will keep jumping and the politicians will keep campaigning – but victims of road traffic accidents will never be stitched up, fistula women will never be dry, and mothers in obstructed labour will continue to struggle and tear and lose their babies and join these neglected ranks.

Unfortunately it wouldn’t take long to put them on the map: there are just a few hundred clinical anaesthetic officers in Malawi, and fewer than five Malawian medical anaesthetists for a population of 16.4 million. (Compared with more than 10,000 for a population of 64 million in the U.K.)

A small group of visiting medical anaesthetists effectively doubles the country statistics.

In August, Lifebox trustee Dr Isabeau Walker travelled with long-time Lifebox friend and president of the College of Anaesthetists of Ireland Dr Ellen O’Sullivan to Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital in Blantyre, in the south of the country.

They were working with Cyril Goddia, who heads the hospital’s Anaesthesia Clinical Officer training programme. A survey he undertook last year with Gradian Health Systems revealed a significant pulse oximetry gap. So we set about a project to close it.

Some anaesthesia colleagues travelled 10 hours to get to Blantyre, from small rural hospitals across the region. They were working without pulse oximeters, or having to share one between two to four theatres. Basic monitoring was a finger on the pulse and an eye on the colour of the patient’s lips…

Thanks to the Cycling Surgeons, who took on hill and dale and puncture in the name of safer surgery, to the College of Anaesthetists of Ireland (COI) who led the faculty alongside our Malawian colleagues, we were able to donate 100 pulse oximeters and deliver training to 80 anaesthesia providers and 20 clinical officer surgeons.

“Thousands of lives will be safer as a result of all your efforts,” Dr Walker reported back. Of the photo from the course – “The smiles say it all!”

Two weeks later we were back in the north, at Kamuzu Central Hospital with ACTS – the African Conference Team led by Dr Keith Thomson. This three-day conference (in the ‘Warm Heart of the Warm Heart’, according to Fanny Mtambo, who supports the UNC Project-Malawi) was an opportunity to improve practice in an area of anaesthetic care that makes up almost 80% of emergency cases: obstetrics.

Think about surgery and (much like toast in a toaster) who comes to mind – the surgeon. But think again about an operation at its most basic level – scalpel rending skin – and imagine it without anaesthesia. It’s the difference between modern medicine and torture, but it’s often overlooked.

This workshop, with support from the Gloag Foundation and UNC, was an opportunity to support the skills, the concerns and the community spirit of a group who know more than any other that something needs to be clear:

“There is no surgery without anaesthesia.”

Explained William Banda, a medical anaesthetist working at Kamuzu: “You can train 100 surgeons – but there will be no operation.”

This shouldn’t be news – but since the message is still lacking, we’re delighted to see that it was!

MBC TV, the main television station in Malawi, sent two journalists and a camera to the conference, to meet the delegates and shine a lens on the vital role of anaesthesia in safe motherhood. It’s possible that they zoomed in on more than expected – a visit to the maternity ward moved quickly from theory to practice – and a gown, mask and a brightly beeping corner of an operating room as a baby was born by emergency C-section.

“Bringing life into this world is an exciting experience,” narrates the journalist, “but at times it can be life-threatening…However there is no surgery without anaesthesia, as anaesthetists play a crucial role in an operation.”

The report was screened twice in 24 hours. What was the response?

“We didn’t know, they say,” explained Marie. “We didn’t know you needed all this to deliver, to survive.”

This is a map of how far delegates at the Lifebox pulse oximetry workshop travelled to get to Blantyre – making the long journey by crowded bus, by bike, from all over the southern region. They came to learn about safer surgery, and take an oximeter back to keep their patients safer.

This is a map of how far delegates at the Lifebox pulse oximetry workshop travelled to get to Blantyre – making the long journey by crowded bus, by bike, from all over the southern region. They came to learn about safer surgery, and take an oximeter back to keep their patients safer.

There are so many more maps we need – where pulse oximeters and training are urgently needed next. Where women wait for fistula repair surgery – or soon will, if they can’t get to a hospital. Where safe surgery is taking place – and where we support the equipment and training to make it evem safer, so that providers and families aren’t forced to make terrible choices to do their jobs or save the people they love.

Till then we’ll be leaving the fish to mind their own business.